Dag Erik Elgin, Photo: RCCL Arts grant

Dag Erik Elgin, Photo: RCCL Arts grant

One of the worlds’ most notable art prizes – the Carnegie Art Award 2014 is being presented a luminary in Norway’s visual art scene: Dag Erik Elgin. The artist’s intellectual and conceptual approach reflects an ongoing investigation of shifting trends in art theory and art history as well as a vital engagement with issues and debates impacting contemporary art.

Elgin is currently working on a large research and exhibition project for the Henie Onstad Kunstsenter (NO) on the provenance of works by Henri Matisse. We talked to him about history, theory, semiotics, and his series Balance of Painters.

In your latest series Balance of Painters you investigate Roger de Piles’ theoretical ideas on art. What do you find so compelling about Roger de Piles?

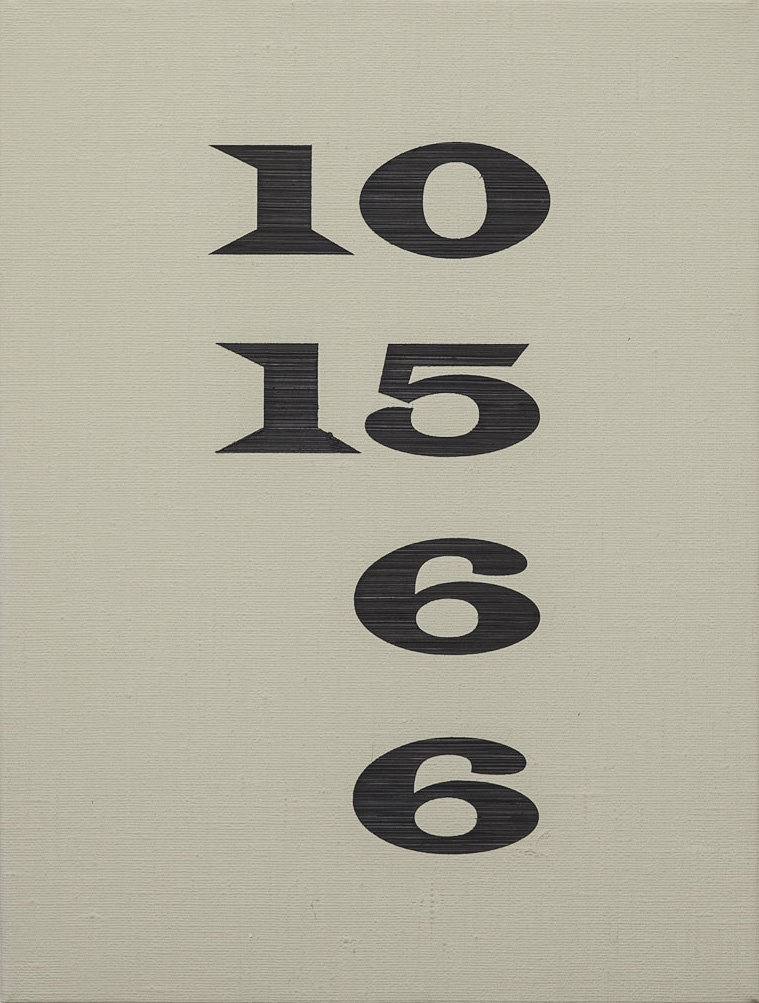

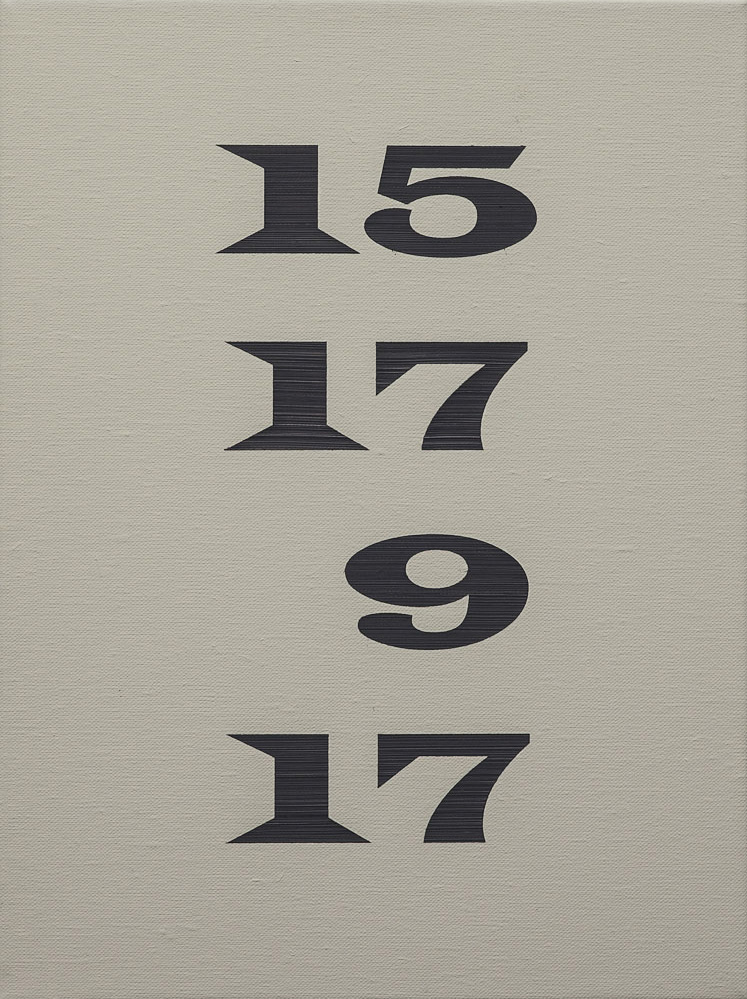

Roger de Piles was a fascinating character with a wide scope of interests, who served as a diplomat, connoisseur, art dealer, and even a spy for Ludwig XIV. As the King’s representative, he had access to the courts of Europe, and since his interests focused on art, court members tended to be off guard. Consequently, de Piles came to overhear secrets of interest to his royal employer, and once he was even imprisoned for espionage. Apart from this side effect of his diplomatic activities, he was an important figure in the art world and wrote a number of influential treatises on painting. In his last work, Balance of Painters (1708), de Piles ranked painters by scoring them from 0-18 in composition, drawing, color, and expression.

Although we may smile at de Piles evaluations today, his categorizations have much in common with the current art world. The rankings of Art Index readily come to mind. De Piles’ system represented a unique possibility to fuse a baroque treatise on painting with contemporary conceptual practices, and it was as if this material was just waiting to be exposed to a painterly investigation.

Balance of Painters (installation view), Studio D. E. Elgin, Copyright the Artist,

Balance of Painters (installation view), Studio D. E. Elgin, Copyright the Artist,

Photo: Oystein Thorvaldsen

What is your intention in appropriating a forgotten art theory of the past? Are you acting as a conservator or re-teller of a specific history?

Painting’s ability to provoke dialogue has always interested me. From Vasari to Buchloh we can trace an unbroken line of texts informed by painting, engaging in massive text-driven painterly post-production. The Balance of Painters is unique in that de Piles actually created imagery in the text when combining numbers to characterize the prominent painters of his day. In doing so, the image was re-established on its own terms within the discourse – as expressed by the term “balance”. For The Balance of Painters is not solely a collection of separate numbers, but rather a precise visual expression of an exact balance between composition, drawing, color, and expression. The paintings address the well-known modernist problematic of figure and ground with the colored gesso referring to classical baroque grounds, while the numbers – in English also referred to as “figures” – are placed onto this “ground”, consequently adding up to “figure and ground.”

Writing and text were important aspects of your earlier works as well. Do you see a semiotic similarity between letters and numbers?

Semiotics describes letters and numbers as indexical signs, a status that changes when they are integrated into a painting. The representational quality of text then becomes a question of painterly execution. This shift that takes place in painting intrigues me, extending from the baroque phylacteries of Pietro da Cortona to conceptual practices of artists like On Kawara, Rémy Zaugg and Art & Language. It is a great strategy to leave space for the viewer to rediscover painterly qualities in an apparently hygienic, or straightforward, boring material informed by the aesthetics of administration.

Balance of Painters 40×30 cm, oil on canvas, Studio D. E. Elgin, Copyright the Artist, Photo: Oystein Thorvaldsen

What role does the spectator play in your work?

Basically, as an artist you are the first spectator of your own work; and to some extent you take future viewers into consideration. However when you are working focused, future viewers seem more redundant. In this gap between communication and cut-off concentration a specific space occurs, a gap that leaves space for the spectator.

How important is the combination of painting and conceptual art to your work? Throughout history all great art has been conceptual in the sense that the artist obviously was guided by an idea about what he or she was doing. However, the term conceptual art naturally refers to a specific historical moment, when the idea of an artwork allegedly came to serve its main constitutive factor. I consider this to be a theoretical post-rationalization. Most conceptual works are in fact not purely conceptual — the concept being the experience of making a particular work instead of solely representing an idea that was known beforehand. In this sense, conceptual art has a great deal in common with painting.

What trends in the conceptual art scene currently interest you?

I see an increasing awareness for the importance of material qualities in contemporary conceptual practices, perhaps because we have come closer to comprehending the sensuous complexity of the works of the classical avant-garde. I am interested in artists informed by and working through this set of problems, who create conceptual works born out of a deep historical conscience.

Interview: Victoria Trunova