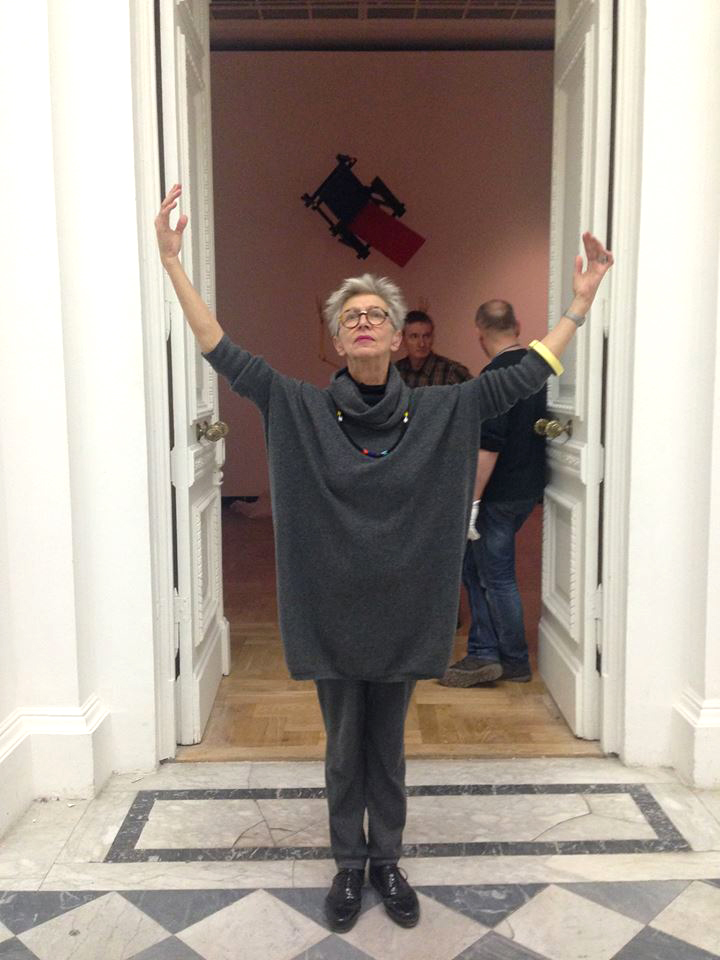

Anda Rottenberg is probably the most well-known curator from Poland today, famous for her critical attitude and the idea of “socially and politically committed curating”. She has been the director of Zacheta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw for many years and is now working as a curator, critic and writer. Her most recent show will be opening on Nov. 28, 2014 in Warsaw and since we are not able to attend the opening, we asked her a few questions about the concept of the show.

The press release of your show entitled “Progress and Hygiene” poses a question as to what today has remained of the idea of modernism and as to the directions in which contemporary modernization is heading. This sentence raises two fundamental problems:

A) Has the idea of progress always been linked to a certain idea of hygiene ? and B) the heritage or legacy of modernism today, does it permit to come up with new ideas about social behaviour?

How do you manage to establish a dialogue between the historical material and documents on questions such as “health, eugenics, social engineering, racial hygiene, national identity, the problem of the “other” and exclusion” and the works of about 50 contemporary artists from Poland and other countries?

The departing point was recently published literature investigating both the side effect of modernists’ ideas and the results of eugenists’ practices in the course of the first part of the XX century. Within the last 15-20 years researches on these and similar subjects were conducted simultaneously in many countries. Before I decided to invite artists, I examined the documents and tried to find links between such fields, like the modernist’s concepts of architecture and urbanism with programs of body health and perfection and further transitions of these ideas on the notions of healthy society based on eugenics.

It occurred that nothing stopped after the WWII, the practice of sterilisation, social engineering, national identity and stigmatization are still present in many countries. It was relatively easy to find documents and combine them with basic, obvious examples of art and architecture: ideas of Hans Richter about the new living, the same approach to beautiful bodies serving their nations (here shown in photos of Rodchenko and Leni Riefenstahl), the chair of Rietveld as a symbol of modernity, etc.

On the other hand many artists approached more traumatic results of the racial hygiene: Gerhard Richter, Luc Tuymans, Miroslaw Balka (who conceived a new piece for this show). Many others were invited to reflect different subjects: Santiago Sierra is showing the situation of stigmatised Indian widows; Joanna Rajkowska stresses the hidden junctions between the weapon and pharmaceutical industries; Jan Fabre is referring to the colonialism of Belgium (in his Congo series), Vadim Zakharov in his new piece refers to the selections and deportations of the Russian intellectuals in the 20s, but it could easily happen anywhere and anytime – to mention only a few.

As to the practice of mixing documents and art objects in the same show, you might have seen it in my Berlin historical exhibition: it works.

Would this show have been possible to curate 10 years ago or could you please describe the urgency of the question and the concept of the show today?

As I have mentioned above, the scientific researches on the subject were published only recently. I don’t think this kind of exhibition would have been possible 10 years ago as many documents were hidden in the archives (some are still forbidden i.e. japanese evidences about sterilisation), but also because the art exhibitions were differently oriented. The urgency is rather obvious: we are facing the radicalization of national, religious, ethnic movements in the large part of the world, including Europe where one may observe growing support of nationalist’s parties.

My personal attention has been focused on ethnic minorities already for several years. I made the exhibition on the national unification process in Nowy Sacz, the native town of my father in Western Galizia (Void, 2012). Last year I made the show in Lublin about the lack of recognition of the smaller nations living in frame of the large unions in the course of history (UNI/JA-UNI/ON, 2013).

In 2011, you have been curating the exhibition “Tür an Tür. Polen-Deutschland – 1000 Jahre Kunst und Geschichte” at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin, Gregor Schneider was part of the show, now you present him with a solo project next to your group exhibition? In how far does his work contribute to a questioning of the fundamental ideas you arouse with your exhibition concept?

I wanted to invite Schneider to my group show when he confessed that he had found the Goebbels’s house in Rheydt. It was clear that this must be a separate project, a sort of particular case complementary to the “Progress and Hygiene”. Only recently it occurred that many books and documents found by Schneider in that house gave the evidence how popular racist’s hygiene was.

Some of the items are exactly of the same kind: phrenological charts, books of Hans Suren, craniometres, habits to examine and improve the body shown on photographs. I think all these were a result of propaganda, the job of Joseph Goebbels.

I also believe that it is a common problem of European intellectuals and artists: what to do with this heritage, still present not only behind the walls of many houses, but in people’s mind.

Try to come and see both exhibitions, Warsaw is not that far from Berlin as people think!

The Interview was held by Ute Weingarten

PROGRESS AND HYGIENE

29.11.14 – 15.02.15

Tuesday–Sunday 12–8 pm

Monday: closed

Zachęta – Narodowa Galeria Sztuki

pl. Małachowskiego 3

00-916 Warszawa