Depicting the “Bizarre” Real World

Interview: Miki Kanai

Esteban Jefferson’s (b. 1989) solo exhibition debut took place at New York’s oldest alternative art space, White Columns—known as a showcase for up-and-coming artists—in 2019. His latest exhibition is showing at Tanya Leighton, Berlin. On display at Jefferson’s first solo exhibition in Europe is the series he has been working on over the past two years about the Petit Palais museum in Paris. Jefferson’s narrative series “Petit Palais” is a reflection on the museum’s collection of largely Western European art and artifacts—spanning the centuries from antiquity to the nineteenth century—as much as its methods of display, which tends to echo the intrinsically colonial gaze of Western European cultural institutions. While Jefferson captures the enigmatic atmosphere of the museum space, it is the artist’s conceptual thought that emerges from his critical gaze.

Jefferson, born, raised and still living and working in New York, has been drawing his whole life; his paintings are still heavily rooted in drawing. Visiting museums and galleries frequently as a child with his architect parents, Jefferson remembers once jumping through sculptures by Fred Sandback at the former Dia Chelsea building and a security guard yelling at him: “Little boy, stop playing with the art!” His parents’ interest in art introduced him at a young age to contemporary art and the possibility of being a professional artist.

Majoring in visual art at Columbia University, Jefferson spent the next six or seven years working as an artist’s assistant in several New York studios. He then returned to school. After this, his work definitely started to coalesce into something unique, he says. He believes this period as a graduate student at Columbia was the breakthrough: he found he could allow himself to leave the work largely unfinished and discovered that the paintings were stronger that way.

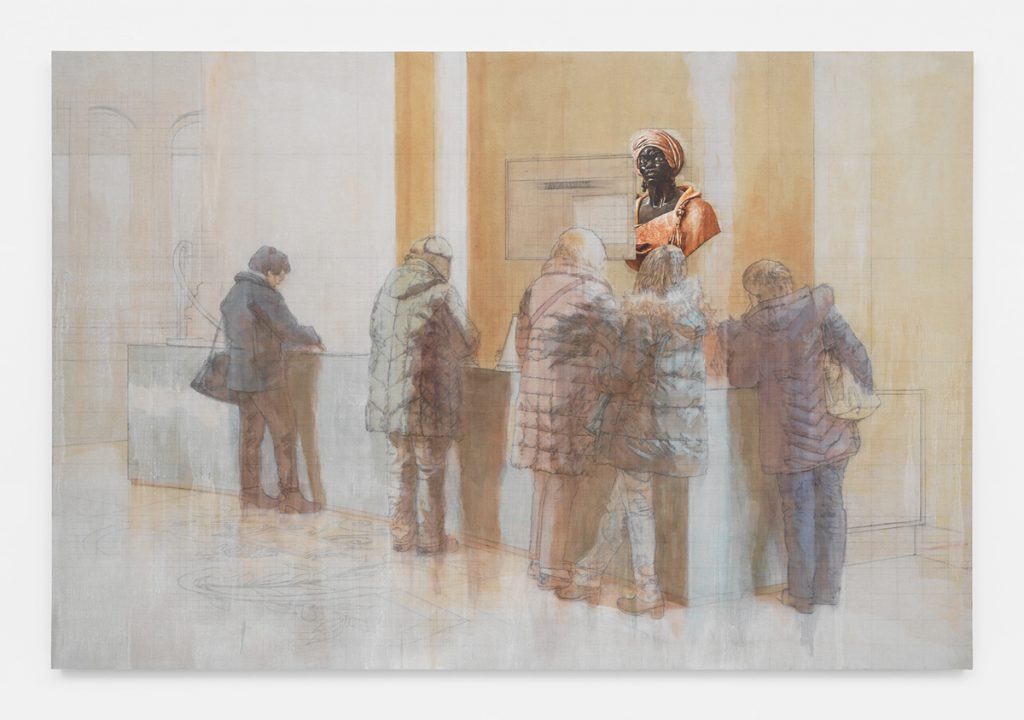

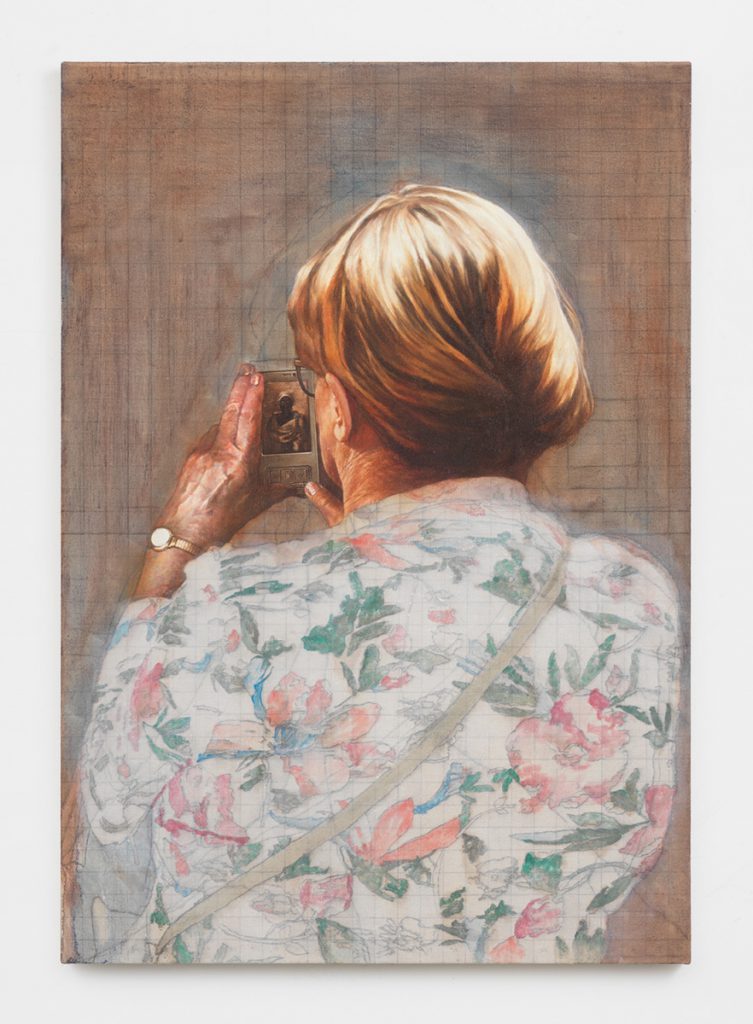

I was delighted to have the opportunity to correspond with Esteban Jefferson by email about his thought processes and first solo exhibition at Tanya Leighton, Berlin. Describing his work primarily as “documentary” or “journalistic” in nature, Jefferson suggests that if the paintings look bizarre, it’s because our world is bizarre. Certainly, the paintings do depict a sense of the bizarre nature of objects. The installation at Tanya Leighton, Berlin presents a reception-like space. One of the paintings depicts a marble bust of an African woman, a woman in profile in the foreground has seemingly taken or is about to take a photograph of the bust—a woman, the “other”—looming in the background, fading out, away. In another of the large-scale paintings, the bust in the background takes precedence over the four viewers’ in the foreground, who are faceless, with their backs to us the viewer.

Miki Kanai: I am curious about the museum narrative in your paintings—how do you go about working with the museum as an institution and the image it portrays—what are your critical points of departure?

Esteban Jefferson: For the past two years, I’ve been working on the “Petit Palais” paintings. Most of it is what you’d expect, except for the two large marble busts of African subjects that are on permanent display behind the museum’s ticket desks. The busts co-occupy their location with haphazard institutional clutter: video screens, reception desks, public signage, and visitor stanchions. While articulating the full space of the museum lobby, my paintings focus on and privilege the serendipitous visual encounters between the museum’s employees and visitors and these two busts. The museum’s wall labels for the busts identify neither their maker nor their subject, nor their date of creation. They’re simply identified as “Buste d’Africain” and “Buste d’Africaine”, but after further research I’m pretty sure they were made in Venice.

The pink and tan colors I use for the atmosphere of the paintings come from the actual marble that covers the entire lobby of the Petit Palais. In the paintings I enhance the distinction between the entire space and the busts, but this is a dynamic that really exists in the museum. That’s what I mean when I say the paintings are documentary.

The long-term goal of the project is to open up a dialogue with the museum, to rethink the way the busts are presented, maybe moving them into a more central space, with updated and fully researched wall labels. As it stands now, the busts occupy the position they always have: somewhat art, somewhat decor, valuable but not valuable, in the same way as everything else in the museum. The irony to me is that the busts are, in my opinion, the most interesting works on display at the Petit Palais.

MK: There is also the essence of art history—you modelled one of your paintings, Flaneuse (2020), on a classic Gerhard Richter painting (Betty, 1991).

EJ: Like Nas said, “no idea’s original, there’s nothing new under the sun, it’s never what you do but how it’s done.” The Richter painting shows his daughter from behind, in a beautiful floral sweater, sitting in front of one of his grey paintings. The artwork she’s in front of isn’t fully articulated in the painting, but it’s implied, so as the viewer, you’re looking at someone looking at an artwork. I love the “echo” of that. I saw a woman in the Petit Palais who happened to be wearing a floral shirt, take a photo of one of the busts, and shot a photo of her from behind. As many times as I’ve visited the Petit Palais, this was the only time I saw someone really notice the busts. I tweaked the composition so that it directly references the Richter painting, and now both paintings follow the same motif of looking at someone looking. The difference is that in Richter’s painting, his daughter is in the studio looking at a work he’s making in the moment; in mine, the woman is looking at an object that has been removed from its original context, and is now floating in empty marble space. If Betty wants to know what the grey painting means, she can ask him. If the woman in my painting wants to know what the bust means, the museum has set up a situation where there is almost no information available about it.

MK: Although your 2019 Chambre Parentale (Parental Room) was in the White Columns exhibition but isn’t on show at Tanya Leighton, Berlin, I would like to learn more about your ideas of the differences and connections between public space (say a museum) and private space (seemingly inside someone’s house).

EJ: That painting depicts an apartment I stayed at in Paris while I was researching “Petit Palais”. The apartment is owned by family friends, and there was about to be a façade renovation done on the building, so at the time everything in the apartment was wrapped in plastic to protect it from construction dust. The dolls depicted in the painting belonged to the owners’ mother, who passed away long before I stayed there. I was interested in the decision to wrap up the paintings, but not the dolls. If the dolls were put in a box in the closet, I never would have seen them; instead, they were left out in the room, meticulously arranged and cared for. I felt like the dolls occupied a similar space to the busts in the Petit Palais; they are valuable, but not in the same way as the paintings nearby. The painting have an art value, and the dolls have a personal value. The dolls have a complex history, and the paintings are pretty straightforward.

I’m interested in how we culturally deal with history, especially uncomfortable histories. In the US there is a long-running debate about what to do with confederate monuments. Do we destroy them and build something new? Do we add overt historical context to them, but leave them intact? Do we remove them but leave their bases standing, as a reminder that they were once there? I think the “Petit Palais” paintings get at these same questions, but within a fine art context; similarly, I think Chambre Parentale gets at that question from a context of personal family history. I’m actually working on an expanded version of that piece now, which will be shown in the spring at the La Trienal, Museo del Barrio, New York.

MK: In the installation at Tanya Leighton, Berlin, a two-channel tourist-style video is running on two stacked CRT monitors, showing the Petit Palais lobby walk-through area and collection, while the faux-marble flooring gives the installation a kind of false grandeur. But there is also a letter to the Petit Palais. How did you conceive this entirety, the structure and installation?

EJ: The paintings were always meant to be shown with the video piece and the “marble” floor. I felt like the video piece grounds the paintings, making it clear that the paintings are taken from things I actually saw at the Petit Palais, rather than coming out of my imagination. The marble floor is meant to bring the viewer physically into the feeling of the Petit Palais. There is a little joke to it, in my mind, because the “marble” that is used for the floor in my show is actually very cheap linoleum we bought from Home Depot; it is a readily available and affordable material, but when it’s installed wall-to-wall I think it captures the disorienting affect of the Petit Palais which is decked out completely in marble very well.

The letter is something new for the iteration of “Petit Palais” that I’m showing at Tanya Leighton, Berlin. I always wanted the body of work to be a vehicle to opening up a dialogue with the actual institution, the Petit Palais, and that letter is my first step towards hopefully working with them to recontextualize the busts. I’ve actually received two responses from the museum, and will be responding again to them soon. I still have some “Petit Palais” drawings that I’d like to make, and by the time those come together as a show, I will hopefully have had a more substantive conversation with the institution. In my mind the project can keep going until the way those busts are curated changes. The wall labels must be updated, and the TVs need to be moved. The busts themselves should probably be moved into a more primary location. But I don’t work in a museum, so I don’t know how feasible these changes are, no matter how strongly I believe they should happen. So this project is me trying to change something that I think is wrong in a museum, as an outsider to that institution, and it is also me learning what the barriers to that kind of change are.

My view is that often we see only what we want to see; we strain to hear the louder voice while ignoring the smaller voice. Alternatively, while we may comprehend the state of affairs, we nonetheless feel compelled to leave it behind. I believe art has the power to shake up our thoughts, it can “nurture” us, help us to gain a clearer perception of the world; it could be said, therefore, that art even has power to “nurture” the art world out of its colonial mentality. Esteban Jefferson’s paintings certainly are powerfully thought-provoking, they made me want to think about what is being depicted, and in its entirety, the exhibition-installation gave me a sense that I was discovering more about what is going on in the “bizarre” real world—I was discovering more about me. The artist applies a conceptual dimension to his painting practice and is relentlessly committed to making his work not only aesthetically beautiful or mysterious as paintings, but also adeptly ensuring they have a profound effect on the world outside the museum, on the viewer, on the world outside their own status as images. I will be following the development of the “Petit Palais” series in the future with anticipation and interest.

Exhibition:

Esteban Jefferson

Esteban Jefferson: Petit Palais

30 October–18 December 2020

Kurfürstenstraße, Berlin

tanyaleighton.com

Miki Kanai, from Tokyo, is a Berlin-based art correspondent. She writes about art and creative culture for Japanese, English, and German magazines, including Geijutsu Shincho, Art Collector, BT/Bijutsu Techo, and Haus der Kulturen der Welt’s 100 Years of Now Journal. She has also coordinated several international exhibitions. After years in art journalism, she is now experimenting with ways of writing about the experience of looking at art on ARTPRESS Blog TALKING ABOUT ART.