by Miki Kanai

Sturtevant (1924–2014) is an American artist whose iconic series Warhol Flowers (1970) is in full bloom at the gallery Société in Berlin. The small and dainty, variously colorful silkscreen works-on-canvas hang on the white walls like postage stamps. Yet the simple, clean hanging of the exhibition (which in my view is perfect) reveals nothing of the convolution the works involve. Maybe it would not do to mount an exhibition in an elaborate setting for a complex artist: These are the silkscreen series of Andy Warhol “by” Sturtevant.

Hate her or love her, despise her or respect her? Sturtevant is the queen of appropriation. It was in the mid-1960s that she began reproducing works by her contemporaries Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Jasper Johns, and so on. In doing this, she successfully raised the question: what do the labels of originality and authorship and the mechanisms that underlie the art world’s structure connote? She shakes the viewers’ belief in authenticity: So much so that we must think, what is it that we are looking at here.

Andy Warhol’s Flowers (1964) were equally conflicted. He took the image of the hibiscus blossoms from a popular American photo magazine Modern Photography, and the photographer, Patricia Caulfield, brought a lawsuit against him for unauthorized use of her image in 1966. Warhol cropped four flowers from Caulfield’s seven in her photograph as illustrated. In the end, Warhol and Caulfield came to an out-of-court settlement and agreed that he could keep using her image.

Sturtevant turned the tables: she could operate the artistic technique of Pop art with her wise and daring hands; she had just as much right to repeat the work of her contemporaries in 1964. She died in May 2014; death did not wait the few months for the opening of the first major exhibition of her work at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, which opened in November 2014. As she could not make the public statement she had planned, some of her statements from the exhibition catalogue allow her a presence now:

—“Having a bit of information, or a name, may stop our curiosity about what we are looking at.”

—“This kind of art has to be worked out at the beginning: it has to start from the molding power of the thought as a sculptural means.”

—“Negative definition is a powerful, valid philosophical position. Additionally, absolute clarity is a rigorous closure.”

From: Sturtevant: Double Trouble (MoMA, 2014)

While at Sturtevant’s exhibition at Société, my thoughts drifted to remembering other paintings of flowers in bloom. Actually, one of the flowers series I was thinking about has a humble surface: toilet paper. Société have recently moved to the ground floor of a lovely building in the Charlottenburg district of Berlin, opening their doors after the first COVID-19 lockdown in June this year. The first show was a solo exhibition by Kaspar Müller titled Mandala. Inspiration for Müller’s paintings came from his six-year-old daughter, whom he saw tracing and drawing around the flowers on imprinted white toilet paper. Facing the huge toilet paper-inspired paintings during a time when people everywhere in Berlin were panic-buying the product seemed absurd at first, but then I imagined children drawing—as practitioners and as adepts of mandala—and painting in an intimate setting, surrounded by family during the lockdown probably. Then, on top of everything else, I perceived the idea of the ready-made versus originality.

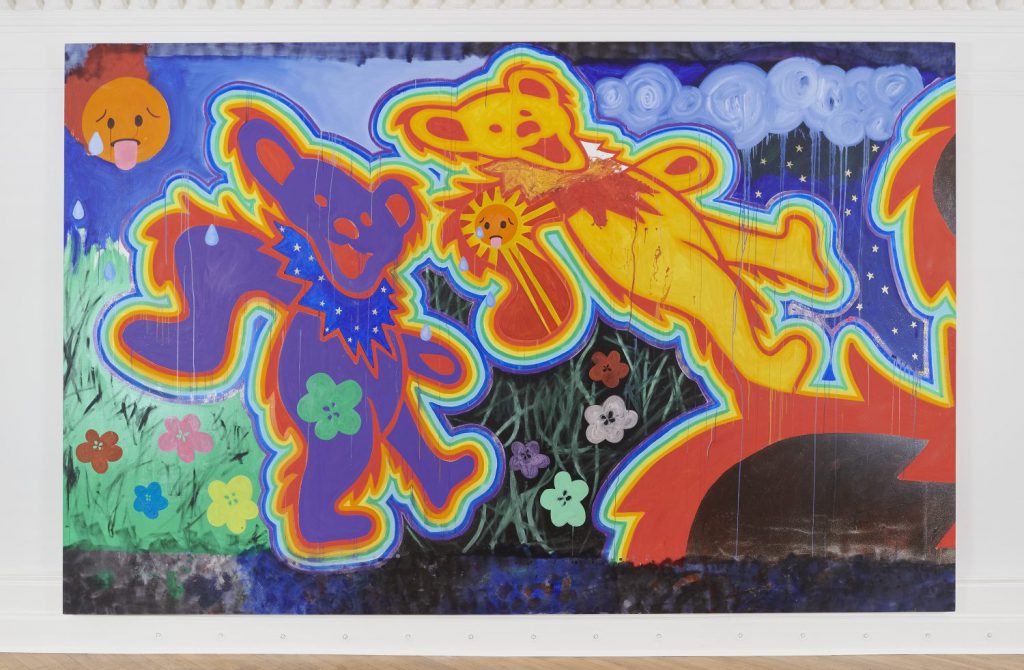

On my way back home from the Sturtevant exhibition at Société, I had a bizarre experience: I came across a sticker of one of the bears of the Swiss artist Tina Braegger on the street near where I live. Should I say the unofficial logo of the Grateful Dead? The bear. It is highly likely that the image multiplies wherever and however after falling from the author’s incessant reminder of sign and symbol. Société represented Braegger and her repetitious bear paintings in a solo show recently, too. At the show, one of Braegger’s biggest works prompted a reaction similar to the type Sturtevant’s Warhol Flowers tend to engender: questions about sign, symbol, authorship, originality, meaning, disassociation, beauty – even painting – all symbolic of the same thing: representation.

Sturtevant’s show at Société has been organized in cooperation with Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac in London–Paris–Salzburg and the Estate of Sturtevant. I found it refreshing; a reawakening, not only a chance to appreciate Sturtevant – whom I believe has been underestimated in art history – with reference to digital simulacra and other women’s right movements in the # Me Too era, but also absorbing her in association with the young generation of artists in the Société’s gallery program.

Exhibition:

Sturtevant

27 October–28 November 2020

Société, Berlin

societeberlin.com

Miki Kanai, from Tokyo, is a Berlin-based art correspondent. She writes about art and creative culture for Japanese, English, and German magazines, including Geijutsu Shincho, Art Collector, BT/Bijutsu Techo, and Haus der Kulturen der Welt’s 100 Years of Now Journal. She has also coordinated several international exhibitions. After years in art journalism, she is now experimenting with ways of writing about the experience of looking at art on ARTPRESS Blog TALKING ABOUT ART.